Many people are spending more time at home these days, which means they may also be rediscovering family heirlooms and artifacts. Others may be looking into their family’s history for the first time. Brushing dust off the boxes in the attic and seeing old photo albums and letters from an ancestor’s past can spark an enthusiasm for family history that lasts a lifetime.

But simply having all the clues in front of you doesn’t mean it’s easy to piece together your family history. Genealogical research entails digging through artifacts from centuries past, and a lot can change in a century. Family members from different eras and continents had their own unique lives and traditions—which can mean your family artifacts might be written in an entirely different language than what your modern-day family speaks.

Anderson Archival sat down with German-English translator Katherine Schober of SK Translations to discuss family histories, digitization, and the joys of genealogy. Schober is a St. Louis native and graduate of Truman State University. Since 2010, she’s been translating family records, letters, and journals from German to English. Her knowledge of genealogical texts and research seemed boundless, so Anderson Archival wanted to find out what challenges family historians might have when encountering historical documents.

Anderson Archival: What is it about the German language specifically that speaks to you?

SK Translations: I knew that I had ancestors from Germany, so that’s where the original interest started. Once I got to high school, I decided to study German instead of Spanish because of those ancestors. I also really love grammar and rules, and German is a very logical, grammatical language. They actually have sixteen different words for “the” depending on where the word is in a sentence!

AA: St. Louis has significant German roots. Can you speak to that as a St. Louis native?

SK: St. Louis has a lot of German immigrants who came over in the 19th century. A lot of Germans at that time said that the hills of Missouri look like the hills of Germany, so they felt like they were at home in their new state. After hearing how happy their fellow countrymen were in Missouri, other Germans then followed and ended up in St. Louis and the surrounding areas. My own ancestors (Wolken) came to St. Louis in 1854, and then a different side of the family (Mueller) came later in the 1880s. We have a lot of German history here.

AA: I’m curious how digitization plays into what you do. What’s your experience working with digitized media?

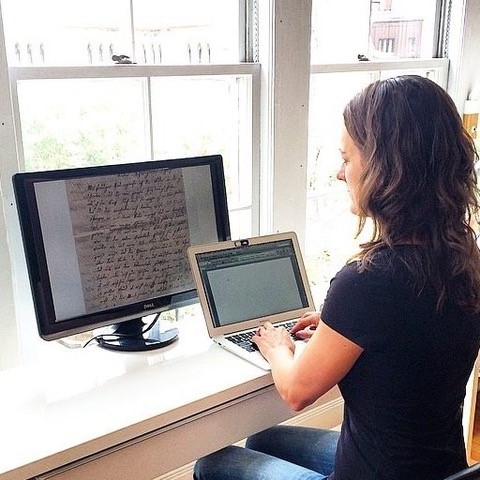

SK: Up until WWII, there was an old type of handwriting [Kurrentschrift] that was used in the German-speaking countries. It’s very intricate and detailed, with lots of small loops and flourishes. In order to be able to read it, I need to really zoom in on those letters. That’s why it’s so important to me that the document is scanned and digitized in very high quality. A lot of times I’ll get documents from clients that aren’t good resolution, and the letters become blurry when I zoom in. At that point, I’ll have to write back and say, “Please scan it in a higher resolution so that I can make out the letters.” They are usually happy to comply, because they want me to be able to decipher their letters as well!

AA: Can you tell me more about that old German handwriting?

SK: Kurrentschrift is the same German language, the same German words, just a different style of handwriting—sort of like how Russian has a different alphabet than we do, although it’s luckily not that complicated. Some letters of the Kurrenschrift alphabet are the same as in modern German, but the majority are different. The “s” and the “e” are especially tricky. My husband, for example, is a native German speaker, and he’s able to read maybe two in five words.

Kurrentschrift was in use until after WWII, and some say that it was Hitler who said he wanted the Germans to start using the “normal” alphabet that you and I learned in school because he wanted people to be able to understand the words in the regions he conquered. He didn’t want the Germans to have one type of handwriting and everyone else to have another. When Germany lost the war, the old handwriting gradually fell out of style in the 1950s.

AA: How would you say that confidentiality plays into the work you do?

SK: I always keep documents confidential unless specifically discussed. Some clients are very open, and sometimes when I work with very interesting documents, I’ll email the client and ask, “Would you be willing to let me share this on my business social media sites for my history-enthusiast followers to see?” Some of them are excited and say, “Oh yes, that would be great, show the world and share it!” and others say, “No, I’d rather keep this private within my family.” I would never share anything without asking the client’s permission first because it does, of course, belong to them and their family. It really is a personal decision of what they feel comfortable doing.

AA: Do you think that’s a big part of choosing to research genealogy in the first place, sharing it with a larger audience?

SK: It can be. I think genealogy is a way to make everyone feel connected. Once you start doing genealogy, it can get very addicting. When you find that first great-great grandparent and realize they were a real person with a real life, you just want to keep going and finding more and more people. And it’s something that’s so exciting to share with others—especially if you find out you are distantly related to them!

I recently translated a letter you may have seen on my blog from 1853. It was from a person who had just emigrated from Germany to move to America, and it was such an interesting letter because he detailed his whole experience of leaving Germany, getting on the ship, the ship journey over, landing in New York, and then getting settled in Brooklyn, NY. I was fascinated by it so I asked my client if she would be willing for me to share it. After I published it on the blog, the response from my followers was amazing, I think because people could picture their own ancestor going through the same experience and were excited to have insight into how that experience might have been.

One of the most exciting things that happened after publishing the letter was one man’s comment that really surprised me. This blog reader wrote that his own ancestor’s name was actually mentioned in the letter. His ancestor was one of the people that the author himself had gone to visit when he landed in New York! My client and that man do not know each other at all today, but it turns out their ancestors were friends, proof of which was in the letter. I thought that was so exciting! Genealogy can really help connect people.

AA: What other kinds of documents do people bring to you?

SK: I work with a lot of church records. In the past in Germany, it was churches who kept track of people’s births, marriages, and deaths. The government didn’t keep track of these life events until the late 19th century, so anyone who’s traced their ancestry back farther than that works with church documents.

I also get to work with a lot of diaries, and those are my favorite because you really get to know a person through their personal writing. I feel so lucky that I get to read their secret thoughts 200 years later! That’s a lot of fun for me because you really feel like you’re getting to know a person and how they lived on a day to day basis. I’m a big journaler myself, and sometimes I think to myself, “Okay, I need to be careful what I write down in case anyone reads this in 200 years!”

AA: What are some challenges with the digital copies people send you?

SK: Sometimes the letter is very creased, and if there’s a big fold in the page it makes it very hard to read. Sometimes the letter is torn so half of it is missing, or there’s water damage to the letter or document. Usually, the thing that I always tell people if they are working with church records, for example, or any other type of records besides a letter or diary, is to send me as much of the document as they can. [I use] not only their ancestor’s records but the records of other people on that page, for comparison purposes. If their own ancestor’s record has water damage or a tear or a crease, then I can look to the record above or below to get a better idea of what words or phrases are missing from their own ancestor’s record.

AA: Have there been any recent projects that you’ve worked on that you’d want to speak to as far as anything that’s been particularly interesting or challenging for you?

SK: I really love the diaries. One of my favorite diaries was set during the early 1900s, written by a woman whose husband was stationed in Thailand in the army. She travelled via ship from Germany to Thailand to go be with him and she kept a diary of her ship journey. She wrote about her life on the ship, and then getting off at different ports and experiencing the culture in the different countries they stopped at. Every page, for hundreds of pages, she wrote, “I miss my husband so much,” “I can’t wait to see him”, etc. So I was really excited for her to get to Thailand and read about their long-awaited reunion. But, much to my dismay, the diary stopped right before she got to Thailand, so I never got to hear how she finally saw her husband again or how their reunion was. It was like a book with the ending torn out!

Just recently I did a letter that was written by a nine-year-old in 1822 and it was really cute. He wrote home to his father and asked him if he could stay at his friend’s house longer and if his father could send him some money because he wanted to buy presents for his friends. That was 1822, but asking if he could stay longer at a friend’s house could have been something a nine-year-old today would say today. That’s something that really strikes me, that humans have really stayed the same throughout history. The circumstances may change, but the basic emotions and feelings and relationships all stay the same.

AA: What other challenges do family historians bring to you? What sort of questions do you hear?

SK: A lot of people get overwhelmed with where to start in their genealogy research. They’ve heard the family stories that their great-grandfather came from Germany, but they don’t know the town he came from or the year he came over, and the people who might have known that information have already passed away. For those people getting started, I would advise them to start with themselves, and then their parents, and then their grandparents, and document from there. A lot of people are tempted to start with the immigrant they heard came over from Germany a hundred and fifty years ago, but because so many people have the same name, or there’s a lot of towns in Germany with the same name, they might end up looking for the wrong person in the wrong town. It’s really important to document everything you know first and then build off that before you just jump in the middle and try to go from there.

AA: What key skills should someone look for when seeking a translator?

SK: The most important thing that a lot of people don’t know is that you should always look for a translator who’s translating into their native language. If you want documents translated from German to English, English should be the translator’s native language because that’s the language they’re going to be writing in and that’s the final product you’re going to get. Then if you’re wanting to go from English to German, you should find someone whose native language is German. You want that final product to be written by someone who has a good feel for writing in their native language.

Anderson Archival is grateful to Katherine Schober for her time and participation in this interview. If you’d like to employ her genealogy translation services, she can be contacted through her website or on her Instagram. Partnering with experts like SK Translations is just one way Anderson Archival keeps your collection’s individual needs on the forefront.

We are dedicated to preserving your history, no matter the language that history may be written in. Even the detailed OCR our archival experts perform needs the expertise of human eyes, especially when written in German.

Language doesn’t have to be a barrier when it comes to family history projects. Contact us today to learn how we can help you tackle your next genealogical challenge.